Since its inception in 1972, UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention has had one objective: to “encourage the identification, protection, and preservation of cultural and natural heritage considered to be of outstanding value to humanity.” Sites are evaluated exhaustively on these merits, and every year about 20 new locales join the ranks of such oft-visited places as Stonehenge, the Galapagos Islands, and the pyramids of Giza. With 17 of Le Corbusier’s most notable projects named to the World Heritage list earlier this month , the UNESCO convention reminded us what an architectural treasure map the list really is. We parsed the sites for a few of our most beloved landmarks to help you plan your next architectural pilgrimage (or two). From neoclassical homes in America’s south to European modernist masterpieces and Moorish mosques, there’s something for every architecture buff. Now get your passport ready!

Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut, Le Corbusier

Ronchamp, France New to the World Heritage list this month, Le Corbusier’s Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut reigns among the architect’s most famous works. The concrete-and-stone structure, completed in 1954, is also known as the Ronchamp Chapel after the eastern French city it inhabits.

Monticello, Thomas Jefferson

Charlottesville, Virginia Finished in 1809, Thomas Jefferson’s neoclassical magnum opus sits atop a peak just outside of Charlottesville, Virginia. The 43-room complex and its gardens were Jefferson’s lifelong projects, heavily influenced by the residential work of 16th-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio.

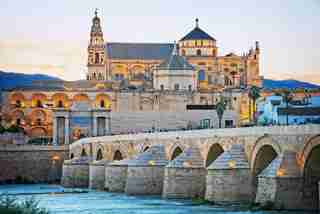

Mosque of Córdoba

Córdoba, Spain Considered one of the finest examples of Moorish style in the Iberian peninsula, the Great Mosque of Córdoba is a symbol of Spain’s tempestuous religious history, having been both a mosque and a cathedral over its years. The mosque sits on the World Heritage list along with the historic center of Córdoba.

Skogskyrkogården, Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz

Stockholm Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz’s Skogskyrkogården was only the second 20th-century cultural site to be named to the World Heritage List. In the construction of the cemetery, the two young architects showed a masterful grasp of the natural landscape and of Nordic Classical style.

Royal Saltworks, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

Arc-et-Senans, Doubs, France Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, the architect lauded for his role in reprising neoclassical style in France, conceived the Royal Saltworks during his time as royal architect in the court of Louis XVI. Ledoux, famous today for many of his Utopian and ultimately unbuilt designs, employed Enlightenment-era principles at Saltworks, including a rational and hierarchical organization of space.

Aachen Cathedral

Aachen, Germany Built around 780 as Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel, Aachen Cathedral sits in its namesake city in Western Germany. The largest cathedral in Western Europe, Aachen melds classical and Byzantine traditions with opulent mosaics and vaulted ceilings. The result is a dramatic religious building that would influence centuries of European design to come.

Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque)

Istanbul The Blue Mosque is one of several Istanbul landmarks on the list (think Hagia Sofia, among others). Perhaps Istanbul’s most notable structure from the 17th century, the mosque is named for the richly colored tiles that adorn its interior.

Rietveld-Schröder House, Gerrit Rietveld

Utrecht, Netherlands A distillation of the early-20th-century De Stijl movement, the Rietveld-Schröder house is architect Gerrit Rietveld’s residential masterwork. Built in 1924, the house marries hyperfunctional design with the inorganic aesthetic principles of De Stijl.

Palladian Villas of Veneto, Andrea Palladio

Veneto, Italy Sixteenth-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio’s fame arose from the neoclassical villas he built in the Northern Italian region of Veneto. Relying on a scrupulous study of classical architecture and in particular, Vitrivius’s De architectura, Palladio’s villas marked a changing tide in residential design, with wealthy Italian patrons preferring a country house that differed stylistically from their typical urban dwellings.

Tugendhat Villa, Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe

Brno, Czech Republic Mies van Der Rohe’s Tugendhat Villa is considered one of the architect’s finest examples of functionalist residential architecture. Completed in 1930 for wealthy Jewish factory owners Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, the house is itself a showcase for Mies’s signature iron frameworks, concrete walls, and open floor plans. It was also the inspiration for Simon Mawer's 2009 book The Glass Room.

Itsukushima Shrine

Itsukushima, Japan Though the Itsukushima shrine that stands today was constructed in the 12th century, the Japanese island is known to have been a holy Shintoism site for centuries earlier. The bright color of the shrine offers dramatic contrast to the landscape, and the arrangement of the surrounding structures shows enormous artistry.

Brasília, Oscar Niemeyer

Brasília, Brazil Developed as an alterative Brazilian capital in 1956, Brasília is a hallmark of 20th-century urban planning and design. Conceived from the ground up by architect Oscar Niemeyer and urban planner Lucio Costa, the city brought to life modernist theories (including those of Le Corbusier) of practical urban living.

Chartres Cathedral

Chartres, France The medieval Gothic masterwork that is Chartres Cathedral is an icon in religious design and considered to be among the most exceptional examples of Gothic architecture in France. Construction began on Chartres in 1145 and was completed nearly a century later, in 1220.

Dessau Bauhaus, Walter Gropius

Dessau, Germany Walter Gropius, Bauhaus founder and arguable father of modern architecture, designed the German school’s headquarters in Dessau in 1925–26. Following his manifesto that buildings should show their interior construction and function, Gropius used a famous glass curtain-wall to reveal the interior of the workshop wing and the support used to construct it.

Casa Barragan, Luis Barragan

Mexico City Famous for his regional interpretation of the modern movement, Pritzker Prize–winning architect Luis Barragan built his house and studio in the Mexico City suburb of Miguel Hidalgo from 1947 to 1948. Barragan’s mastery of light, space, and color are clear in the residence, which has come to influence decades of architects, including most notably Barragan’s contemporary Louis Kahn.

Leave a Reply