In many ways, design today is treated as avenue to inclusion. Architects beautify and reconceptualize affordable housing , devise public spaces that bring art out of galleries and to the masses, and create environmentally conscious structures to preserve our planet’s dwindling resources. Likewise, the set creating such design is diversifying. But the process is, and was, far from organic. As is the case with most necessary stepping stones on the way to progress, individual boundary-pushers are vital—those willing to disrupt convention and welcome the spotlight, if not only for themselves.

African Americans were long barred from the architecture profession; from the higher-education institutions that granted degrees to the firms that excluded based on race alone. Today’s African American architects and designers did not arrive by wave of wand, or even as the conventional narrative would say, gradual progress. For this we thank controversial Supreme Court rulings, schools willing to make exceptions, and the most essential: driven and unafraid black students, unafraid to tolerate a swarm of flashbulbs on their first day of classes, or graduate without the support of the trade itself. Though laws regarding segregation have since evolved, architecture is still often fairly critiqued for its homogeneous makeup. Here, AD recognizes some of the most influential African American architects who were trailblazers in their own ways, leaving a mark on the built world for years to come.

Norma Sklarek (1926-2012)

Once called “the Rosa Parks of architecture” by AIA board member Anthony Costello, Harlem-born Norma Merrick Sklarek overcame racism and sexism to become the first licensed black female architect in New York in 1954, the first black female member of the AIA in 1959, the first licensed black female architect in California in 1962, the first black female Fellow of the AIA in 1980, and cofounder of the nation’s largest woman-owned architecture firm (Siegel Sklarek Diamond) and the first black woman to co-own an architecture firm in 1985. As an architecture student at Barnard College and Columbia University, she was one of two women and the only black student in her 1950 class, and upon graduation was passed over for several jobs (“They weren’t hiring women or African Americans, and I didn’t know which it was [working against me],” she is quoted as saying to a local newspaper) until she landed a role with the Department of Public Services, then at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and then Gruen Associates in Los Angeles. She collaborated often with Caesar Pelli on iconic structures such as the Pacific Design Center (pictured) and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, before cofounding her own practice with Margot Siegel and Katherine Diamond. “Architecture should be working on improving the environment of people in their homes, in their places of work, and their places of recreation," Sklarek said of the practice. "It should be functional and pleasant, not just in the image of the ego of the architect.”

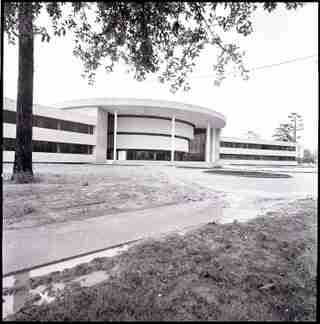

John S. Chase (1925-2012)

On a hot June day in 1950, Associated Press photographers clamored around a 25-year-old John S. Chase as he waited in line at the University of Texas at Austin. One of the first two African Americans to enroll in the school’s architecture program—just two days after the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate professional and graduate schools—Chase was already making history even if, to him, this was merely an exciting step in his professional life. Chase went on to become the first black architect to be licensed in Texas, and began his own practice after receiving rejections from the white-owned firms in the area. Known for modern designs and democratic public spaces, notably churches, some of Chase’s most well known projects include Riverside National Bank—the first black-owned banking institution in the state of Texas—the U.S. Embassy in Tunisia, the Martin Luther King, Jr. School of Humanities at Texas Southern University (pictured above), and the Phillips House residence in East Austin. To promote the work of people of color in architecture and design, Chase cofounded the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) in 1971.

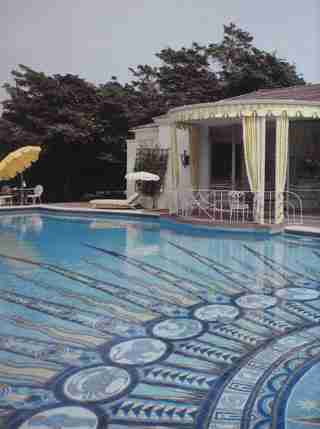

Paul R. Williams (1894-1980)

Known as the “architect to the stars,” Los Angeles–born Paul R. Williams is a Southern California legend who designed over 2,000 homes in his more than 50-year career. Williams’s architecture was often distinguished by a mix of styles, and his oeuvre spanned typologies: from hotels and restaurants to churches and hospitals. Though advised by a high school teacher that he would not get enough work as a black architect, Williams pursued architectural education at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and training at several prominent L.A. firms before starting his own practice and becoming the first black member of the American Institute of Architects, in 1923. His celebrity clients were Hollywood’s It crowd, including homes for Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, and Barron Hilton (shown here), and his work outside the state spread Hollywood glamour to the rest of the nation. In 2017, Williams was posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal; wrote architect William J. Bates, FAIA, in his support: “Our profession desperately needs more architects like Paul Williams. His pioneering career has encouraged others to cross a chasm of historic biases.” As Williams wrote in his 1937 essay for The American Magazine : “Without having the wish to ‘show them,’ I developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself.’”

Robert R. Taylor (1868-1942)

Born in Wilmington, North Carolina, a 20-year-old Robert R. Taylor traveled to Boston to sit for the MIT entrance exam, determined to study at the university’s school of architecture. Four years after passing the test, he became the first academically trained black architect, and the school’s first black graduate. During his course of study, he met Booker T. Washington, who later recruited Taylor to lead the industrial program and campus expansion at his Tuskegee Institute, an African American vocational school in Alabama that is now a designated National Historic Site. Over his lifetime as an educator and architect, Taylor designed more than 25 buildings on the Tuskegee campus, including Washington’s own home (seen here), as well as libraries, housing, museums, and other academic buildings in North Carolina, South Carolina, Ohio, Arkansas, Mississippi, Virginia, Tennessee, and in Liberia.

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

At 27 years old, architect, engineer, and urban planner Beverly Loraine Greene became the first black female architect licensed in the United States—in Illinois in 1942. She started her practice in Chicago; however, when racial prejudice caused her to be often passed over for projects and ignored by the media, she moved to New York City to work, ironically, on the Stuyvesant Town housing project: In 1945 it did not allow African Americans to live in its apartments. She would go on to push past further barriers, working with some of the most well-known international modernists on iconic structures—with Edward Durell Stone on the Sarah Lawrence College arts complex and Marcel Breuer on the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (pictured). In her final project she designed several buildings for New York University but died before she saw their completion.

John Warren Moutoussamy (1922-1995)

After graduating from the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1948, where he studied under Mies Van Der Rohe, John Warren Moutoussamy began a fruitful architecture career in the greater Chicago area. One of Moutoussamy’s most high-profile commissions was the headquarters for black publishing titan John H. Johnson’s growing media empire, which included Ebony and Jet magazines. Inside the stone-clad structure, colorful walls and psychedelic carpets exuded energy, celebrating black culture and commerce. Today, it remains the only downtown Chicago tower designed by an African American. The city landmark—still known to many as the Johnson Publishing Building (seen here)—is currently undergoing a conversion into rental apartments, though the emblematic Ebony / Jet signage will remain.

Moses McKissack III (1879-1952)

The grandsons of a trained builder, Moses McKissack III and his brother Calvin followed in family footsteps. After studying architecture via correspondence courses, the Tennessee-born siblings became the first (Moses) and second (Calvin) black architects licensed in their home state in 1922. Together, they formed McKissack & McKissack, the nation’s first black-owned architecture firm, and the oldest still in operation today. At first, most of the firm’s projects were churches or church-based; however, in 1942 they won a multi-million-dollar federal contract to design the Tuskegee Army Airfield, the largest project that had been awarded a black-owned firm to that date. Today, the family-owned firm is known for its design and construction management, recently for the National Museum of African American History and Culture (pictured), designed by British architect David Adjaye .

Walter T. Bailey (1882-1941)

Born in the small town of Kewanee, Illinois, Walter T. Bailey was the first African American graduate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in 1904, and went on to become the first licensed African American architect in the state. Between 1905 and 1916, Bailey helmed the mechanical industries department at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he designed several buildings on campus before leaving the university to open his own practice, which focused mostly on commercial projects, churches, and renovations, including contributions to what is currently called the Pleasant Street Historic District—a hub of the African American community in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Bailey’s last major project was the now-landmarked First Church of Deliverance in Chicago (pictured), an unconventional Art Moderne building clad in glazed terra-cotta, which he completed in 1939.

Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885-1949)

For Lexington, Kentucky–born Vertner Woodson Tandy, design ran in the family: His father was a respected mason whose firm built his hometown courthouse, among other prominent structures. After attending the Chandler School and the Tuskegee Institute, Tandy matriculated into Cornell to study architecture, where he was a founding member of the nation’s oldest African American fraternity. He would soon become the first black architect registered in New York state, where his landmarked structures include the 1910 St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Harlem (shown here)—the first black Episcopal church in New York and the second in the United States—which he designed with his firm partner George Washington Foster, the first black architect registered in New Jersey.

Leave a Reply