Like far too much of animal life, many bird species—one in eight, according to a recent study —is facing a real and imminent threat of extinction. And for those not yet in those immediate crosshairs, the struggle for life has become much more of a struggle, as food sources dwindle (and become toxic), habitats disappear, environmental regulations get scrapped, and invasive species present new challenges—all in the context of a changing climate that demands new adaptations. On top of these already considerable challenges, there is another culprit responsible for an increasing share of bird deaths: architecture.

Birds, especially during seasons of migration, will confuse the reflection of buildings and inadvertently fly into windows.

“Between 300 million and one billion birds die each year from building collisions,” says John Rowden, the director of community conservation at the National Audubon Society. “Across the country, birds face multiple threats,” he explains, “but they also have to navigate our built environment, where they are especially challenged by light pollution and glass surfaces.” Architects are now starting to take this challenge seriously, designing building enclosures that mitigate bird collisions. As Rowden explains, “the good news is that incorporating bird-friendly design can reduce collision deaths by up to 90 percent.”

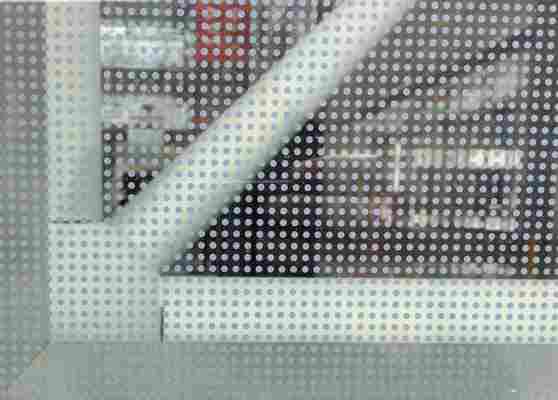

An interior look at the space, with Midtown Manhattan in the background.

Those statistics are borne out with a recent high-profile project—the renovation of New York’s Javits Center, an immense 760,000-square-foot exhibition hall clad entirely in glass. Situated along the Hudson River, on Manhattan’s far West Side, the James Ingo Freed–designed building was long a New York landmark, but it also carried a macabre point of distinction: being the building responsible for the most bird deaths per year in New York.

A close-up view of the glass shows the detail that went into ensuring the exterior was bird-friendly.

A recent renovation by FXCollaborative replaced the entire facade, transforming what had been a dark-mirrored glass into a surface with greater transparency and clarity. As the firm’s director of sustainability, Dan Piselli, puts it, “we reduced bird collisions by 95 percent.” The architects did this by using glass with a subtle fritted pattern, which not only averts bird collisions, but also cuts down on solar heat gain for the building’s vast interior spaces. A new green roof adds vegetated nesting and feeding space on the waterfront site.

An aerial view of the Javits Convention Center shoes a green roof that adds vegetated nesting and feeding space for birds as well.

As Piselli sees it, this is a design challenge that will only become more prevalent. “An increasing number of buildings are being built near habitat,” he says, “and an increasing proportion of those buildings are clad in glass.” Governments are taking notice, too. Just this year, U.S. representatives from Illinois, Virginia, New York, and Tennessee introduced the “Bird-Safe Building Act,” which would require new federal buildings to incorporate bird safety into their designs.

Leave a Reply