The desert rose has long been symbolic of great mineral beauty found in a barren climate. Pritzker Prize–winning architect Jean Nouvel has described the desert rose as “the work of the wind and of the sand for millennia.” When the architect was tapped to construct the new National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ), he drew from the country’s history: “Qatar has a deep rapport with the desert, with its flora and fauna, its nomadic people, its long traditions,” he says. “To fuse these contrasting stories, I needed a symbolic element. Eventually, I remembered the phenomenon of the desert rose: crystalline forms, like miniature architectural events, that emerge from the ground through the work of wind, salt water, and sand. The museum that developed from this idea, with its great curved discs, intersections, and cantilevered angles, is a totality, at once architectural, spatial, and sensory."

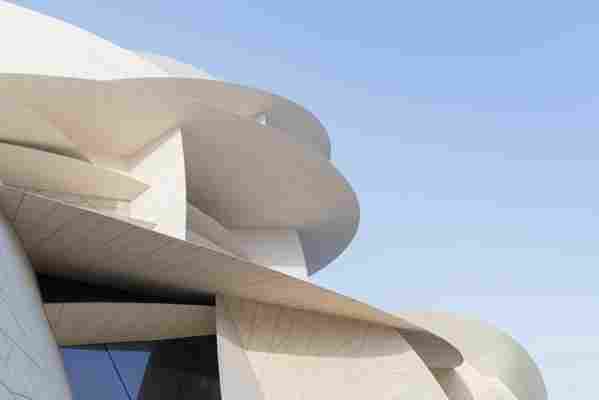

A close-up view of the interlocking discs of the new National Museum of Qatar, inspired by the shape of the mineral desert rose.

The desert itself is the bedrock of Qatar—the nation’s very foundation and image. Only relatively recently, when oil was first discovered in Qatar, in 1940, did its capital, Doha, form itself into a glittering constellation of towers. Inspired by this delicate mineral symbol, Nouvel created a new building embracing the nearby reimagined historic palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, son of the founder of modern Qatar. The result is a $434 million, 430,000-square-foot structure that defies the conventions of a traditional art museum. The nation’s latest cultural treasure, located across from the Corniche waterfront in Doha, is a noble endeavor 10 years in the making, officially opening to the public on March 28. The historic home of the royal Al Thani family was also once the seat of the government and the former site of the country’s original National Museum and aquarium, from 1975 to 1996.

Nouvel recently tweeted that the entire museum is “architecture to give a voice to heritage while celebrating [the] future.” Its façade is both modern and classic: a pale-colored Jenga-meets-Kandinsky structure with interlocking discs that look like supersize versions of delicate petals, made of 250,000 fiberglass structures beautifully set in 76,000 panels.

The museum will be the first notable structure visitors see in Doha as they arrive from the airport. It has 11 permanent galleries, each offering a 360-degree immersive experience into the natural, anthropological, and paleontological history of a nation whose geological narrative started more than 700 million years ago. The vision was to deliberately move away from a static museum narrative to a more dynamic one that takes into account Qatar’s current identity, explains Sheikha Amna bint Abdulaziz bin Jassim Al Thani, director of NMoQ.

A view of the restored historic Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, together with a close-up view of the new National Museum of Qatar.

In a nutshell, it is a chronological journey organized in three chapters: beginnings, life in Qatar, and building the nation. The chronological journey starts well before any human habitation existed and continues to the present day, culminating in what Al Thani believes is the nerve center of modern Qatari identity: the restored palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani.

The complexity of the country echoes throughout the exhibits. Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, chairperson of Qatar Museums and daughter of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, who was emir of the nation until 2013, notes that the country “is a land that has hosted many past civilizations. While it has modernized its infrastructure, it has still remained true to the core cultural values of our times.”

Visitors can expect to find rare objects, such as the Pearl Carpet of Baroda, which reflects Qatar’s multidecade history in the pearl-fishing trade. The carpet was commissioned in 1865 and is embroidered with more than a million and a half fine Gulf pearls, and is heftily adorned with emeralds, diamonds, and sapphires. Visitors will also see the oldest Koran discovered in the country, in the 1800s.

A close-up view of the interlocking discs of the new National Museum of Qatar.

Apart from the architecture, uneven floors, and pearl-like grace of the building’s interiors, the museum’s specially commissioned artwork and films really stand out. Elaborate gardens bright with blooms circle the restored palace. Was the contrast of real flowers juxtaposed with the architectural desert rose symbol intentional? Definitely. Nouvel has remarked that there is a method behind the seeming madness of the museum’s architecture.

One of the core missions of the museum is to impart lifelong learning to its guests, and it accomplishes this by conceptualizing and establishing intergenerational learning for school-age children as well as adults. Multilayered exhibits are often interactive, offering not only an immersion of sight, touch, and sound but also of aromas. There are tales of Bedouin life, with vivid imagery and film; rich, evocative scenes of nomadic desert life; and brilliant images and exhibits of life in Qatar today. Visitors also have access to a digital archive, with thousands of images, videos, and documents from all over the world that have helped shape the current Qatari identity.

A view from the restored historic Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani into the courtyard of the new National Museum of Qatar.

Despite being a national museum, it has an unmistakable international identity. In its sprawling outdoor space, known as the “Howsh,” there is a sculpture by Iraqi artist Ahmed Al Bahrani. The park dances with an impressive installation by French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel, who created 114 fountains set in a lagoon complete with streams designed to evoke the graceful strokes of Arabic calligraphy. Othoniel, who created black bead-like curlicues that mimic the lines of the museum itself, was in constant dialogue with Nouvel and his vision. Also in the park is a sculpture by Syrian artist Simone Fattal called Gates of the Sea —an ode to the Al Jassasiya petroglyphs in Qatar.

This cultural debut is just one of the pearls of the country's upcoming attractions: Also on the horizon is the 3-2-1 Qatar Olympic and Sports Museum, and the country is preparing to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Recently, Qatar debuted the Museum of Islamic Art, along the Corniche.

Below is Architectural Digest ’s exclusive interview with Jean Nouvel on the new National Museum of Qatar.

AD : How different is this project for you compared to the Louvre in Abu Dhabi? Are there any notable similarities to share?

Jean Nouvel: There is much more contrast here. In museums, there is always the idea of creating a neutral space so that it doesn’t mute the exhibits. Here it is not an art museum, but a history museum. There is narrative with very diverse sequences that go along perfectly with the historical discourse and the various objects from different periods.

AD : Since the immersive sensory experience is paramount to the overall aesthetics of the new Qatar Museum, how did that affect the overall architecture and design?

JN: No, they have absolutely no influence on each other. These are two different architectures, dictated by two different contexts, and again with highly contrasted situations. Ultimately this is also one of the point of architecture, to emphasize the differences and the relevancies.

AD : Could you please describe any particular details on executing your vision of the "desert rose" aesthetics? Any challenges that you faced or notable accomplishments?

JN: The desert rose is a symbol; it’s not a reality; it’s not something that is described in details, it is an unknown typology of space, based on a random system of intersections, unknown from the inside. It creates a new aesthetic, a kind of surprise when you move from one space to the other and each time you need to reorient and give a direction and meaning to the presentation accordingly to the given space. It allows you to create different scales with different lights, different understandings so it actually helps the expression.

Obviously, when you choose to go with this symbol, you face some difficulties. You need to solve some modularity issues, those of a museum and of a construction. You need very powerful computers to face the problem of randomness and bring it to a common denominator. Only the most sophisticated computer, recently created, allows this, so it was a lot of work to go from the idea to the reality.

AD : What do you want visitors to take away from this new museum in Qatar?

JN: The memories of an unknown place, symbolizing the encounter of the desert and the sea, an unknown place symbolizing Qatar, its contemporary dynamics but also its belonging to the elements: the water and the sand; the light and the shadows; the wind on the desert rose and on the wild and indigenous flora.

The National Museum of Qatar opened on March 28, under the patronage of Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, and led by its chair, Her Excellency Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani.

Leave a Reply