As firefighters risked their lives to keep Notre-Dame cathedral from collapsing this past Monday, one imagined them fighting to save not only a building but an iconic symbol of France's greatest achievements and cultural heritage. With France itself teetering on the edge of political and economic upheaval, it seemed symbolic of the country's fight to keep a grip on the tenuous connection between its past and an uncertain future.

The future of the cathedral itself—and particularly its spire—is likely to be drawn into a similar debacle. No one is debating whether Notre-Dame should be rebuilt, of course. The moment it was clear that the cathedral's towers had been saved, President Macron promised it would be. Within 24 hours of the blaze, $650 million for repairs had already been pledged from people such as Bernard Arnault, chief executive of LVMH, and companies such as Apple. And today, the French government announced that it will hold an international architecture competition to replace the collapsed spire. Notre-Dame, which was undergoing a $170 million restoration at the time of the fire, will live to see another chapter in its life.

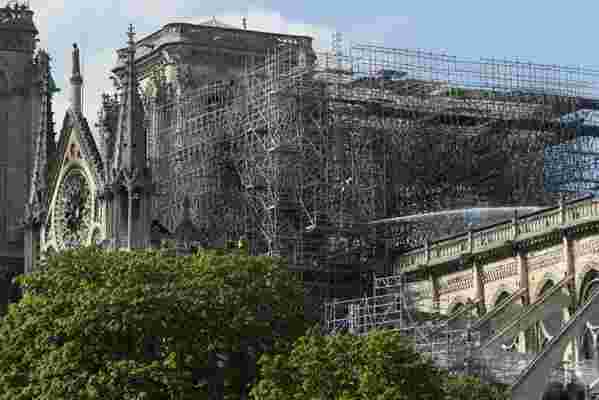

Once immediate concerns are addressed—a makeshift roof must be temporarily installed and relics and artworks moved elsewhere for safekeeping—the question is, what will the long-term process of rebuilding look like? Should the custodians of Notre-Dame try to restore and replicate exactly what was lost, or move into the future with materials and aesthetics that speak to our current time and technology?

Notre-Dame's spire, which was added to the cathedral's roofline much later than many might suppose. “What we're really seeing is a 19th-century building that looks like a 13th-century building,” says Jacqueline Jung, associate professor in Yale University's department of history of art, of the iconic building before Monday's fire.

Construction on the epic Gothic structure began in 1163 and was completed around 1240. While few primary records of the building process exist, one architectural historian recently laser-mapped the cathedral , recording every nook and cranny. While that may make it easier to replicate various sections of the building, it's no surprise that many materials used to build Notre-Dame centuries ago are no longer relevant or available. Take, for example, the 13,000 trees used to create the cathedral's roof and framing, which came from primary forests. Comparable timber simply isn't an option. While most experts agree that the craftspeople and knowledge exist to re-create various sections of Notre-Dame, if construction materials and techniques are radically different now, should the aesthetics of the rebuilt structure reflect our modern times, or merely replicate a style from the past? In the announcement for the spire contest, officials noted that winning designs will have to be adapted for contemporary materials. That may be an indication that the new spire will look entirely different than anything from the past.

Such questions are sure to be hotly debated in the coming months and years. To answer them, it's helpful to think of the cathedral as a living monument that already has seen extensive changes throughout the course of its nearly 850-year life. For example, the spire that tragically burned and toppled Monday was not original to the cathedral. It was added during a contentious 19th-century restoration project by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who sought not to preserve the fabric of the original building, but to visually calm the chaotic complexities of Gothicism. In doing so, Viollet-le-Duc was revising history on his own terms.

Jacqueline Jung, associate professor in Yale University's department of history of art, points out that the version of Notre-Dame we are most familiar with looks quite different than the original structure. “What we're really seeing is a 19th-century building that looks like a 13th-century building,” she tells AD .

A closeup view of Notre-Dame's most severely damaged sections. A makeshift roof must be temporarily installed and relics and artworks moved elsewhere for safekeeping.

Rebuilding a spire that already represented an inauthentic version of historic architecture begins to feel like an odd choice for some. “If you do so, you're sort of falsely creating history,” says Meredith Cohen, associate professor of the history of art and architecture in the department of art history at UCLA. “You can't re-create the past, so don't even try,” says Cohen. Instead, she suggests that France should “build something that harmonizes” but that is aesthetically relevant to the modern era.

Some historians argue a familiar building that looks like it did previously relieves viewers of uncomplicated juxtapositions that make it easier to compartmentalize history. But an inauthentic reincarnation could feel like a Disney-ified version of Gothic architecture that glosses over its bumps and warts.

“Any building that has existed for 1,000 years goes through major transformations,” says Jeffrey Murphy, a partner at Murphy Burnham & Buttrick Architects, who led the restoration process at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City. Regardless of style, Murphy says, a patchwork of materials can impact the evolution of a building over time. “There is a certain honesty that you can convey through preservation.”

“There's an opportunity to make this building more resilient, make it safer and a more sustainable building,” adds Murphy. “As an architect, I'm optimistic that they'll be able to bring this building back.” Weaving an apt and accurate tale of history through Notre-Dame's next iteration will surely be an ongoing challenge. But ultimately, says Murphy, the most important question is, “How do we make this building go for another thousand years?”

Leave a Reply