Whether it’s deserving can be debated, but today’s major architects are often associated with showmanship and ego. For many, to win a competition is a must, and being distinguished with the world’s biggest awards becomes a necessity. And there’s no bigger award than the annual Pritzker Architecture Prize. Indeed, it is to architecture what the Nobel Prize is to literature. Which is to say, the field’s highest honor. While this year’s winner, Japanese-born architect Arata Isozaki, might not be a household name, his work appears sturdy enough to stand the test of time. The designs of this year’s laureate can be seen across the globe, from the high-profile Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles to the lesser-known Nishiwakishi Okanoyama Museum in central Japan. What links these two ingenious works of architecture across a great yawn of the Pacific Ocean is Isozaki’s use of solid geometric forms to create buildings that command our attention—not for the space they occupy, but rather the clarity and purity they espouse.

The announcement of Isozaki as the 2019 recipient means that his name will be uttered in the same breath as past laureates in the great canon of Pritzker Prize winners, such as Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, Philip Johnson, Oscar Niemeyer, and Norman Foster. Today’s announcement also means, of course, that it will be yet another year until other major architects such as David Adjaye , Daniel Libeskind , César Pelli , David Chipperfield , and Diller Scofidio + Renfro can lay claim to the award.

The Qatar National Convention Centre in Doha, designed by Isozaki in partnership with RHWL Architects

Certain principles must not just be realized but mastered in order for an architect to win the Pritzker Prize: firmness, commodity, and delight—three rules favored by the ancient Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. It was Vitruvius’s view that buildings should not merely represent beautiful objects but enhance the quality of life for those who come in contact with them. Since opening his firm in Tokyo in 1963 at the age of 32, Isozaki has a catalog of buildings that stand as a testament to Vitruvius’s creed. Isozaki, who has built museums, towers, bridges, libraries, furniture, corporate offices, pavilions, sports complexes, concert halls, and college buildings, among other structures, finds inspiration in not the grandness of the edifices he designs but the void of them. “Extravagance is, for me, complete silence,” said Isozaki . “Nothingness, that is extravagant.”

The exterior of a shopping district in Milan designed by Isozaki and Zaha Hadid.

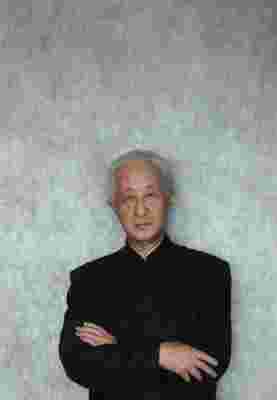

With white hair and a deliberate manner of speaking, the architect has an air of serenity. Yet looks can be deceiving. After all, Isozaki has been labeled in his country as Japan’s “guerrilla architect” for his ability to add visual puns to his designs. Isozaki’s work boasts irony that verges on the edge of altruism. This is most aptly displayed in his design for the Fujimi Country Club in Oita, Japan. The architect fashioned the roof into a giant question mark that begged the question: Why are the Japanese so hell-bent on using their country’s limited land to build golf courses?

A portrait of the 2019 Pritzker Prize-winning architect, Arata Isozaki.

The aftermath of World War II occurred during Isozaki’s formative years in Japan. It was during this time that his country was occupied by the United States, an episode that went on to define the architect’s style. “I am of the generation that grew up under the occupation of the United States,” said Isozaki . “I grew up in a traditional Japanese atmosphere, until all of the sudden, Americanism arrived. That’s why [my work] is quite ambiguous.” While Isozaki has stated that he was against the United States’ occupation of Japan, it hasn’t curbed the criticism he receives from the more conservative factions within Japan who see him as a man who’s adopting Western architectural forms while neglecting his roots. Those who favor Isozaki's vision would argue, however, that the architect is the very embodiment of Japan's dilemma: how to be Japanese and Western at the same time.

Completed in 1990, the Isozaki-designed Palau Sant Jordi has since become an iconic structure in Barcelona, Spain.

Last year, the 2018 Pritzker Prize was awarded to architect Balkrishna Doshi . The architect rubbed shoulders with and learned from some of the biggest architects of the 20th century, such as Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. The 2018 announcement was historic for a swell of reasons, not least of all that it was the first time the committee awarded the prize to an Indian-born architect. With Isozaki, however, it won’t be the first time a Japanese-born architect has won the Pritzker. In fact, Japan is now tied with the United States for the most Pritzker prizes (eight). This means, of course, that the architect carries on the legacy of previous winners from Japan: Shigeru Ban (2014), Toyo Ito (2013), Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, SANAA (2010), Tadao Ando (1995), Fumihiko Maki (1993), and Kenzō Tange (1987).

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles, designed by Arata Isozaki.

It’s the last name in that esteemed group, however, that impacted Isozaki’s career the most. Tange (1913–2005) combined traditional Japanese motifs with modernism, influencing not only Isozaki but also luminaries such as Kengo Kuma. Yet the relationship between Tange and Isozaki was a special one: The most recent Pritzker Prize winner started his career under Tange. The elder’s mentorship lasted until 1963, when Isozaki left to found his own firm.

The Thessaloniki Concert Hall, designed by Arata Isozaki, located in Thessaloniki, Greece.

The exciting news of Isozaki winning the prize comes just days after Kevin Roche, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect in 1982, passed away at the age 96.

Leave a Reply