Twenty stories of objects and areas in people’s homes that nourish their souls more than their social feeds. Read them all here throughout August.

I inherited a tablecloth a few months ago and with it, the most tangible link to my family’s past. It is white, crocheted with an intricate and beautiful design, and it’s been in my family for generations. It was crocheted by my great-great grandmother, a Montana native born in 1886. Her mother, my great-great-great grandmother, was Indigenous; a member of the Blackfeet Nation. Her father was an Irish immigrant. She crocheted her heritage— my heritage—into this tablecloth.

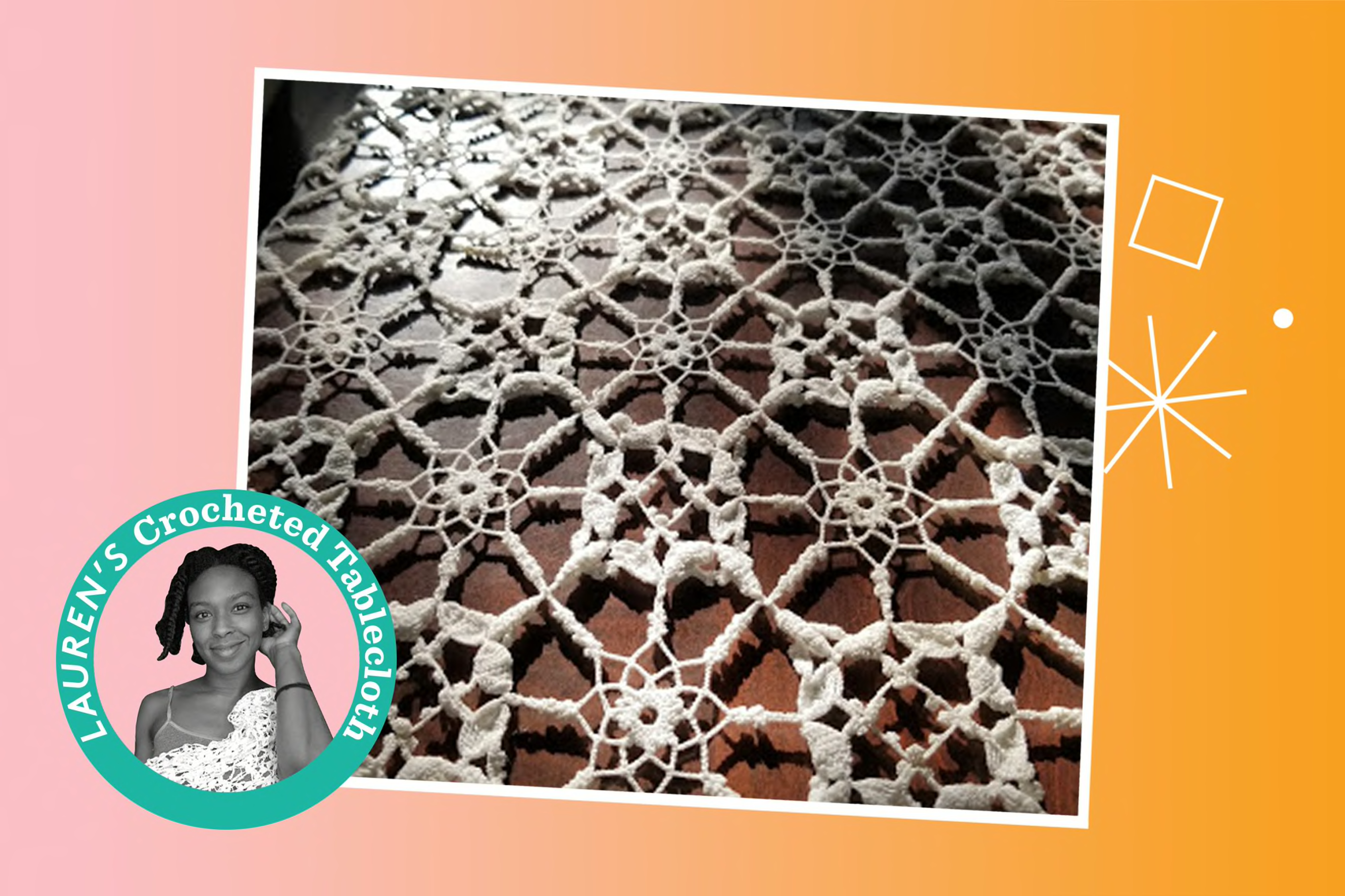

The tablecloth is nearly six feet long and five feet wide, and my great-great grandmother wove it with an ornate pattern that incorporates two symbols: One a symbol from her Indigenous mother’s culture and the other a symbol from her immigrant father’s. It’s covered in generations-old stains, indicative of the family dinners it’s endured. Stitches have broken, leaving noticeable gaps in the aesthetic, but the pattern and symbolism remain prominent.

I am Black. My people are Black. And being Black in America often means not having the privilege of knowing your ancestry. Even through storytelling, we can’t possibly know everything about our lineage. And we often don’t have memorabilia to connect us. But I own this tablecloth—a keepsake with some semblance of who I am and where I come from. But even still, it’s an incomplete picture. This piece of connection is only from my maternal lineage, and it only dates back 100 years. It is just a small piece in the rich mosaic that is my heritage. The rest remains a mystery, a tragic reality for most Black folks.

To be able to hold something made by the hands of my maternal ancestor is magical. I feel the labor that she put into making this tablecloth. I know it was intended to endure the generations; it resonates with strength. I feel the love that she put into making this tablecloth. I know she was thinking about me when she made it; it resonates with ancestral love.

Just before I received this inheritance, I heard the ancestors call to me. They told me it was time for me to speak. To use my voice and speak up for myself and my people. I responded with hesitation and fear—what if I don’t know what to say? They told me to not be afraid; they would be there to guide me. Soon after—and unknowingly—my mother gifted me with this tablecloth. A physical representation of the ancestors that I could keep with me always.

My tablecloth now lives in my office, and I no longer use it as a tablecloth. Instead, I use it as a gateway to connection. Its presence encourages me. It reminds me of the hardships my people have endured and the strength we needed to do so. It grounds me, reminding me of who I am and where I come from. It connects me. Reminding me that I am not alone; the ancestors are always here with me.

It sits folded neatly on the bookshelf in my office, the centerpiece of my small, but growing, ancestral altar. I see it daily. My desk faces the bookshelf, and though my sightline is obstructed slightly by my computer screen, every once in a while, the whiteness of the cloth catches my eye. I believe it’s the ancestors ensuring their presence. When I feel lost, misguided, or disconnected, I’ll pick up the tablecloth, wrap myself in it, and ask the ancestors for help. It reminds me to keep speaking because so often they didn’t have voices. It reminds me to be happy because unbridled joy was not an emotion that many had the privilege of feeling. It reminds me to give thanks because I’m alive when there were so many forces working against me being here. And it reminds me that rips and stains don’t show weakness, rather endurance and strength; it tells me that we may tear, but we don’t break. I’m so thankful to have this beautiful, tangible connection to my roots.

I am the fifth generation to hold this piece of memorabilia. And when I have a daughter, I will give it to her, so that she may have this privilege that is offered to few Blacks: to know a piece of where she comes from.

Leave a Reply