The Japanese architect Junya Ishigami is known mainly through photos of his work. Seeing that work firsthand meant traveling to Kanagawa (outside Tokyo), where a forest of 300 thin columns holds up the roof of his KAIT Workshop, or to Yamaguchi (near Hiroshima), where he is creating an underground restaurant as a series of caves, their roofs supported by earthen stalactites. (A visitor center at Park Vijversburg, 93 miles northeast of Amsterdam, though elegant, seems less daring than the Japanese projects.)

But Ishigami’s visibility will increase dramatically on June 20, when London’s Serpentine Gallery unveils its latest summer pavilion, which he designed. Previous Serpentine Pavilions have attracted up to 250,000 visitors, the gallery has said.

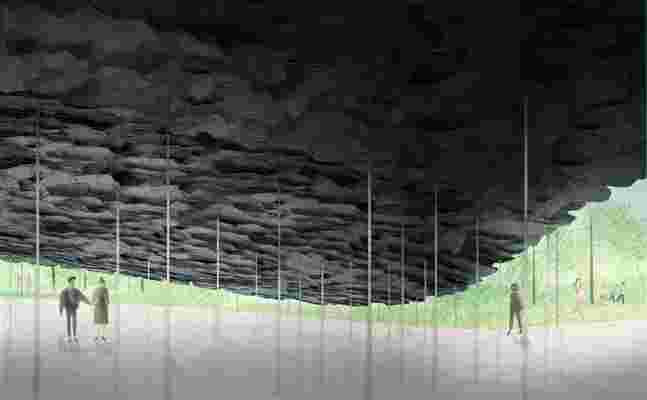

For his summer in the spotlight, Ishigami plans to create a roof of thin sheets of slate, sheltering a cave-like space and suggesting a new geologic formation. The building, in Kensington Gardens, will look “as though it had grown out of the lawn, resembling a hill made out of rocks,” he said in a press release. Some of the best Serpentine pavilions—an annual series that began in 2000—have blurred the line between architecture and nature, and the line will be particularly fuzzy this summer.

Serpentine Pavilion 2019, Design Render, Interior View.

The 2019 pavilion will be a celebration not just of Ishigami but, in effect, of three generations of Japanese architects. In 2002, Toyo Ito designed what the British architecture critic Rowan Moore has called “perhaps the most satisfying of Serpentine pavilions,” a steel structure composed of seemingly random, angular patchworks of solids and voids.

In 2009, Ito’s proteges Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, of the Tokyo firm SANAA, designed an amoeboid aluminum roof that, raised on toothpick columns, seemed to drift like smoke among Kensington Gardens’ trees. And in 2015, Sou Fujimoto, a protege of Sejima and Nishizawa (and thus a member of the third generation of Japanese architects chosen by the Serpentine Gallery), built a formation of white-painted “sticks” that resembled a cloud more than a building. The transition from Ito to SANAA to Fujimoto to Ishigami seems to represent steadily increasing levels of abstraction.

The question for Ishigami (who is four years younger than Fujimoto) is not whether he can dazzle visitors. He has done that with a five-story metal balloon filled with helium, a 30-foot-long tabletop that seems to levitate and a white frame said to be so thin that docents dressed in black were needed to make it visible. The question is which side of the art/architecture line he’d like his work to fall on. The Serpentine Pavilion will, like almost all of Ishigami’s creations, have little function other than to delight, and perhaps that’s okay. Like an artist, Ishigami seems to believe that form follows fancy, not function.

Leave a Reply